Escaping the Builder's Trap: Build the Business System First

Infra founders love perfect code, but markets only care about outcomes. The real system to be built is the business itself, not just the tech inside it. If you're shipping feature after feature and watching adoption stay flat, you might be in the builder's trap. Here's why it happens, and what to pay attention to instead.

Technical founders often fall into a common pattern. They optimize the cleanest part of the stack, the software itself, and treat everything essential for distribution and adoption as "a problem to be solved later." This approach misses a critical reality: the business is itself a system. It functions as an engine of feedback loops, where only the outermost loop connecting to the market truly sets the speed limit. Building a feature is easy; building one that moves a business metric is a different game entirely.

The operational tug-of-war, then, is almost always between the "Market Loop" (will anyone care?) and the "Build Loop" (can we ship it?). The trap is letting the build loop's own gravity pull it away from the market's orbit. This is particularly easy to fall into for a certain kind of founder.

If you're a systems founder, you know the pull. That's the archetype, right? You build keystone primitives where the real value only shows up after multiple, complex pieces are wired together. This naturally drags you into "builder mode." It's not that you don't "get" markets; it's that the sheer complexity of your vision can stretch the feedback loop so long that your contact with the market decays to zero.

The journey feels intoxicating. Every problem you solve seems to uncover a deeper, more fundamental one. You find yourself on a quest of technical, conceptual, and user discovery all at once. This is the hard, meaningful work, the intellectual puzzle. You might be architecting for decentralized value sharing, designing a global public ACL, or wrestling with how to guarantee cryptographic provenance in an era of bots. It all feels essential. And one day you realise you spent 10 years digging into that rabbit hole, and you also realise, it will never end. There is no perfect solution, only trade-offs.

Real impact demands running both loops in parallel, so that solving the problem can be done with work-in-progress capital-flywheel.

The Concurrent Loops

Impact = Build Loop x Market Loop

- The Build Loop - This is your comfort zone. It's about creating an elegant, secure protocol. The metrics you track are technical: time-to-provision an identity, mean-time-to-revoke a credential, signed-claim throughput. The anti-pattern here is subtle but deadly: you keep adding surfaces to the protocol faster than any single use-case can become undeniable. You end up with a beautiful engine for a car nobody is ready to drive yet.

- The Market Loop - This is the one that often feels foreign. Its only job is to find a paying customer with a painful, first-order problem today. It's not about selling the grand vision of trust federation; it's about solving something mundane and expensive, like eliminating static secrets in CI/CD pipelines or managing cross-organization vendor access. The metrics here are about cash and customers: the number of active design partners, weekly jobs run on your platform, and verified ROI stories.

Mastering that second loop is where things get tricky. Every time you try to solve a fundamental problem you uncover while working on a smaller one, your complexity doesn't just grow, it multiplies with your uncertainty. Each new component you add to the system introduces not only its own set of technical unknowns but also an exponential number of unknown interactions with everything else. That's the cost curve: the more foundational your project gets, the more unknowns you accumulate, not just in tech but in how customers will react, how a supporting ecosystem will be built, and whether you can even explain what you've made. The smartest teams get tripped up by this paradox. Sometimes being "dumber", artificially limiting scope, keeping things simpler than your intelligence tempts you to, is what lets you make real progress. Learning velocity beats speculative perfection every time.

Rabbit Hole of Complexity

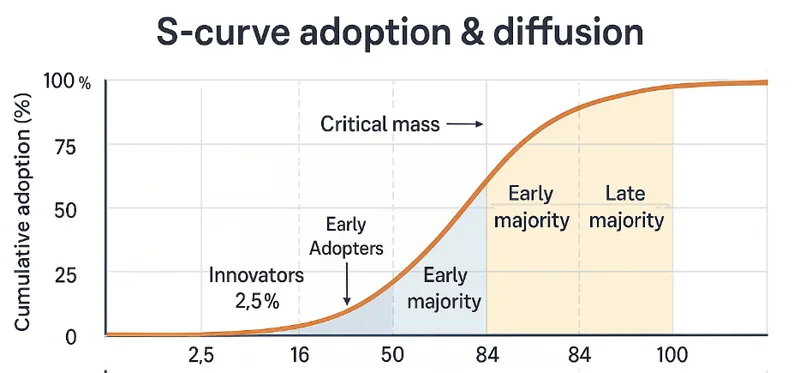

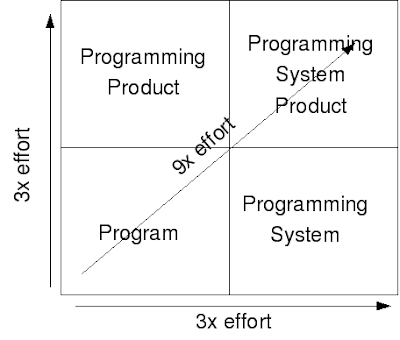

This feeds directly into the tyranny of complements. When you plug into existing systems, you inherit a world of support: distribution channels, documentation, common mental models, and all the complements are already baked in. But when you build greenfield protocols, every missing piece: SDKs, admin panels, policy languages, even basic "how-to" guides, is another steep hill to climb. Each absent complement quietly blows the complexity budget and pushes the adoption S-curve further to the right. The effort required to turn a mere "program" into a robust "product" that people can use, and then into a "system" that can be built upon, doesn't just add up, it multiplies. You see this pattern everywhere. A system with immense potential dies because the surrounding ecosystem didn't show up at the same time.

Staring into that top-right quadrant is terrifying. It's Fred Brooks' famous "tar pit," where great engineering ambition goes to die, bogged down by a nine-fold effort multiplier. Faced with this reality, it can feel like the only rational response is a massive, non-consensus bet that sidesteps the problem entirely. But there's a trap inside the trap: mistaking being non-consensus for just being contrarian. The real edge isn't knee-jerk disagreement, it's reading further out on the chain of consequences. It's seeing the second- and third-order effects, the non-linear jumps that never show up on a burn-down chart.

Cutting the Gordion Knot

An operational improvement is a linear gain. The non-linear, paradigm-shifting return comes from discovering how that improvement unlocks a new, composable primitive that can ignite a network effect.

To make this concrete, consider an example from our work in decentralized security and verifiable outcomes. The first-order effect of replacing static secrets with dynamic, sigchain-based capabilities is an operational improvement: a smaller attack surface and less audit toil. That's the linear gain. But the true non-linear leap happens next. With a system like this, each action, a code deployment, a data access, a command to an AI agent, can now generate a cryptographic receipt: a discrete, verifiable artifact of what happened, signed by the actors involved.

At first, these receipts are just better internal audit trails. But when they become a common, interoperable language for trust, a network effect begins. Suddenly, you're not just building a security tool. You're building the foundation for a new utility for verifiable outcomes. Security policy becomes programmable, composable and auditable across entire ecosystems. A "deployment receipt" from your CI/CD system can be used as direct evidence for a cyber-insurance policy. A vendor can prove compliance to a customer without sharing proprietary logs. The focus shifts from managing keys to trading on verifiable truths.

That is the leap. The question isn't "How do I outsmart the herd?" but "What is about to become inevitable if these interactions compound for another six months?" Consensus thinking usually means you're just optimizing for a local minimum.

Principles are Simple and Ancient, Execution is Difficult

This brings us to the real job of the founder. Entrepreneurship here is less about having a "vision" and more about designing and owning feedback loops. It's the agency to decide when to expand or contract the system boundary. Sometimes "build tech" is the right call. But the decision to make repeatedly is when to pull back and let the needs of the first-order "Market Loop" lead.

This is a delicate balancing act. The day-to-day operational reality is an iterative, often mundane process of getting the first-order business right. It's about cash flow, customer retention, and solving one real problem so well that someone pays for it. But to attract capital and talent, you must also be able to tell the nth-order story, the epic narrative of how your verifiable receipts and network effects could change an entire industry. That's "narrative financing," and it's essential for selling the vision.

The entrepreneur's real edge is living in both timelines at once, using the proof from the mundane first-order reality to make the epic nth-order story credible. It's bet-sizing: knowing which small, iterative experiments will resolve the most uncertainty for the least effort, and being okay with leaving the rest to entropy until the time is right.

The signals that you're escaping the trap are tangible, because the loops start to couple tightly. Market feedback shapes the roadmap in weeks, not quarters. "Shipping" becomes less about pushing raw features and more about releasing artifacts that generate real, external proof. A stable core emerges, one that attracts the complements it needs without the team having to brute force everything. The narrative shifts from "what does it do?" to "what does it let us accomplish?" That's when adoption starts to compound.

These positive signals stand in stark contrast to the familiar warning signs of the trap. Most are old news, just dressed in new clothes: premature generality and protocol romanticism, driven by an obsession with the "Build Loop". You see infinite proof-of-concept limbo, where the "Market Loop" never gets a chance to close. Activity becomes a stand-in for evidence. Energy is spent making things more elegant rather than more useful. The business system drifts while the technical system gets ever more intricate.

Sun Tzu's The Art of War fits on a few dozen pages. Its principles are famously simple: know your enemy, know yourself; avoid what is strong, attack what is weak. Yet for 2,500 years, generals with this knowledge have still lost battles.

The gap between knowing the principle and executing it under fire is where everything lives. It's where companies, armies, and careers are made or broken.

The real work of execution happens in the messy middle, in the constant, difficult arguments over questions that have no easy answers:

- How much uncertainty should we carry at once?

- When is it worth accepting dependency on an existing framework, even if it cramps our technical ambitions? (Our experience is that external dependencies sometimes don't do what they say in the README and can cause expensive refactors later when integration is not an easily reversible decision, so rather than trusting the label, use AI to do a deep due diligence...)

- What's "enough" surface area for our platform to be viable right now, and when do we stop adding more?

This framework, then, isn't a map with a destination marked "X". It's a compass and a shared language. It's a tool to help you have the right arguments and make conscious trade-offs in real-time, rather than defaulting to what's comfortable. It externalizes the psychological battle, turning a personal feeling of being trapped into a systems-level problem that the team can diagnose and solve together.

If there's a discipline to any of this, it's in using that compass relentlessly. It's in drawing and redrawing the system boundary, managing feedback loops, and owning the complexity you choose to take on. The business is the system, and the code is just a means, not an end. Build the business system first; let the code follow where it's needed.